Welcome to Pillar #1 of the Concurrency & Multithreading: The Ultimate Engineer’s Bible series.

Imagine you’re sharing a bank locker with three roommates. You all trust each other, but you only have one key. Why? Because if everyone accessed the locker at the same time, it would lead to utter chaos — stuff might get stolen, broken, or lost. That key is what we call mutual exclusion in the world of multithreading.

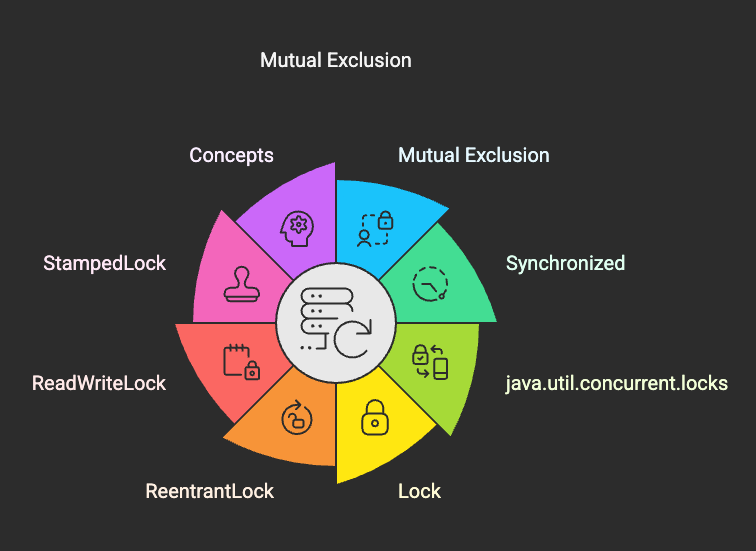

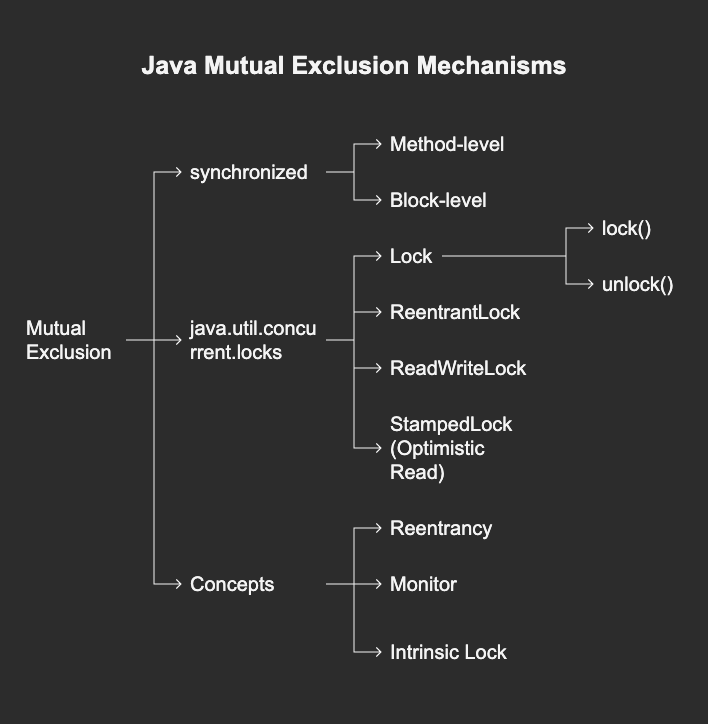

🧱 What Is Mutual Exclusion?

In a multithreaded system, Mutual Exclusion (Mutex) is the principle that ensures only one thread accesses a shared resource at a time. It’s about guarding a critical section of code so that no two threads execute it simultaneously, thereby avoiding data races and ensuring thread safety.

Why Is This the First Pillar?

Because if you don’t get mutual exclusion right, nothing else matters. Visibility, atomicity, coordination, all come after. If multiple threads corrupt your shared data, everything else is just damage control.

🔐 Java Mechanisms for Mutual Exclusion

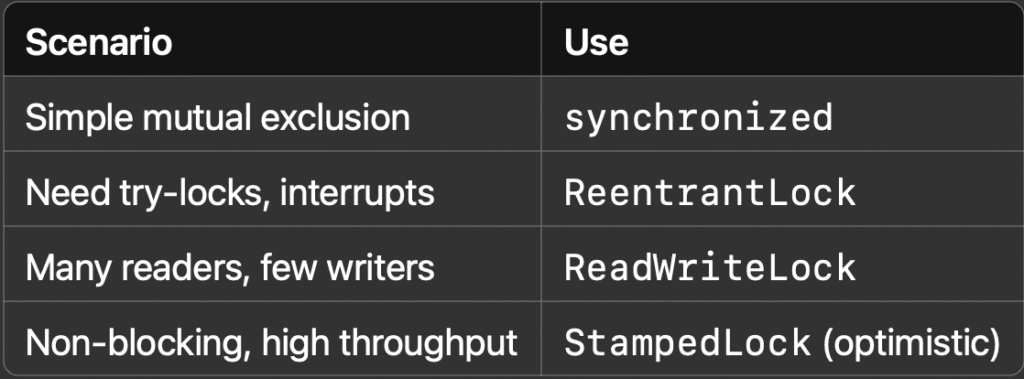

1. synchronized — The OG Lock 🔓

This is Java’s built-in lock mechanism. Simple, elegant, and native.

Method-Level Locking

public synchronized void deposit(int amount) {

balance += amount;

}Here, the lock is on the object itself (this). Only one thread can call any synchronized method at a time on the same instance.

Block-Level Locking

public void deposit(int amount) {

synchronized (this) {

balance += amount;

}

}Fine-grained control — only the critical section is locked.

🧘 Analogy: Imagine you’re booking a conference room. Method-level locking is like locking the entire building. Block-level is just the room itself.

2. java.util.concurrent.locks — Precision Tools 🛠️

Lock Interface

Unlike synchronized, you must explicitly acquire and release the lock.

Lock lock = new ReentrantLock();

lock.lock();

try {

// critical section

} finally {

lock.unlock(); // Always in finally to avoid deadlocks

}Why use Lock?

- It gives you tryLock() to avoid waiting forever.

- You can interrupt the waiting thread.

- Fine-grained control.

ReentrantLock 🔁

Allows the same thread to acquire the lock multiple times — like recursive method calls. Supports fairness policies too.

ReadWriteLock 📖✍️

Optimized for scenarios with many readers and few writers.

ReadWriteLock rwLock = new ReentrantReadWriteLock();

rwLock.readLock().lock();

// multiple threads can read

rwLock.readLock().unlock();

rwLock.writeLock().lock();

// only one writer

rwLock.writeLock().unlock();StampedLock

🕵️ (Optimistic Reading)

Better for high-performance reads — comes with tryOptimisticRead().

StampedLock lock = new StampedLock();

long stamp = lock.tryOptimisticRead();

int value = sharedValue; // read without locking

if (!lock.validate(stamp)) {

// fallback to pessimistic lock

stamp = lock.readLock();

try {

value = sharedValue;

} finally {

lock.unlockRead(stamp);

}

}🧠 Deep Concepts You Must Understand

Reentrancy 🔁

A reentrant lock allows the thread holding the lock to re-acquire it. Think recursive functions or nested calls.

Monitor ⛩️

Every Java object has a monitor — an internal mechanism used by synchronized. When a thread enters a synchronized block/method, it acquires the monitor.

Intrinsic Locks 🧬

These are the internal locks tied to each Java object. Used by synchronized, but not visible or controllable like Lock objects.

⚠️ What Happens Without Mutex?

// Thread A

balance = balance + 100;

// Thread B

balance = balance - 50;If both threads read balance = 1000 at the same time:

- A computes: 1000 + 100 = 1100

- B computes: 1000–50 = 950

- Depending on who writes last, final value can be 950 or 1100 — but it should be 1050!

⚒️ When to Use What?

💡 Tip: Always prefer synchronized for simplicity unless you need advanced locking features.

🚨 Common Pitfalls

- Forgetting to unlock: Always use finally block.

- Nested locks = Deadlocks: Be cautious with lock order.

- Locking on this in shared classes: Exposes internals to accidental misuse.

🧘 Analogy Recap

- synchronized = Room with an automatic lock.

- Lock = Manual lock with full control.

- ReentrantLock = You can unlock a door you already opened.

- ReadWriteLock = Library rules: many can read, one can write.

- StampedLock = Ninja-style: read fast and quiet, check if anyone noticed.

🛤️ What’s Next?

You’ve just mastered the first pillar of concurrency. In the next post, we will dive deep into:

🔜 Pillar #2: Visibility — where volatile, the Java Memory Model, and Atomic* classes reside.

Stay tuned.

🧭 Series Navigation

🛠️ Show Your Support

If this post brought you clarity, saved you hours of Googling, or challenged the way you think:

- 🔁 Share it with a fellow engineer or curious mind.

- 💬 Comment with questions, feedback, or requests — I read every one.

- 📩 Request a topic you’d like covered next.

- ⭐ Follow to stay ahead as new deep-dive posts drop.

Pingback: Visibility: The Hidden Force That Breaks or Builds Your Code - ByteByteNews

Pingback: The Ultimate Java Concurrency & Multithreading Roadmap (Deep, Transferable, Timeless) - ByteByteNews